Yet most animals, including Blackbirds, use the natural ebb and flow of daylight to determine their annual cycles, such as breeding, moulting and migration. Towns and cities are artificially lit up 24-hours a day. The two together can mess up a bird’s diurnal and annual rhythms and interfere with its ability to communicate. The first is light pollution, and the second is noise pollution. There are two factors prevalent in cities, though, that are particularly challenging for wild animals. The breeding season is extended, and Blackbirds in cities are less prone to migrate away in winter (as they would in many European locations) because there is more food available and, of course, it is invariably warmer than in the countryside. There are more positive differences, too. In the case of the Blackbird, it breeds at much higher densities in towns, as if it were aping the human arrangements. Those that are, though, don’t stay exactly as they are some of their behaviour changes. Today’s urbanised sprawl provides enormous challenges for wild animals, and many are not up to it. It was a remarkable feat of adaptation and, since the populations in town and country don’t seem to differ much genetically, a remarkable feat of plasticity in behaviour. Yet, some birds managed to swap the boughs for the balconies, and the rustle of leaves for the human hubbub. Had you been allowed to predict its ecological future back then, you probably wouldn’t have picked it as a pioneer it is a bird seemingly at home in deep deciduous forests, where many individuals still thrive. The Blackbird has been a staple of the urban environment in Europe for a remarkably long time, since the start of the 19th Century, 200 or so years. Not the Blackbird, that of the constant euphonious spring soundtrack of the concrete sprawl. They can only be enjoyed by the few, not the many (to misquote that famous phrase). Some of the world’s most gorgeous songs – that of the Hoopoe Lark is a good example – are tucked away, virtually unheard, into rarefied habitats, such as desert. Another factor, which also confers deep resonance to us humans, is that the song is a staple of the built environment – it’s enjoyable because it’s there.

It isn’t only the richness, variety and tone of a Blackbird, though, that makes it such a pleasure to listen to. In theory, therefore, you could get a clue as to your local Blackbird’s age if you listened thoroughly enough, with younger birds having simpler songs! The sheer variety among individuals should also mean that, with practice, you could learn the songs of the birds around you. In most other species that have been studied, such as the Chaffinch, the song is set in the individual’s first year and doesn’t become enriched. Their repertoires increase with novel input – they will sometimes incorporate copied phrases from first-year birds – so a three-year-old Blackbird will have a richer vocabulary compared with a younger bird. Studies of Blackbird song have also revealed something unusual – individuals get better as they get older. Each individual male Blackbird (the females don’t sing) has a repertoire of at least 100 song-phrases. These endings vary enormously, and allow for a dash of mimicry, not always of another bird, but even bells or human voices. Each phrase is a discrete production, with a significant pause from the last, and no phrase is immediately repeated (making it very different to the Song Thrush’s song.) Listen carefully and you might notice that each phrase begins with glorious contralto fluty notes, but ends much less tunefully, with a squeak or chuckle. There is no doubt that the Blackbird is one of Britain’s finest songsters. There are times when, during a particularly stressful day, I have put on a recording of a singing Blackbird and allowed it to wash away life’s frustrations. I find the virtuoso notes and the wondrously unhurried delivery not just pleasing on the ear, but on the psyche, too.

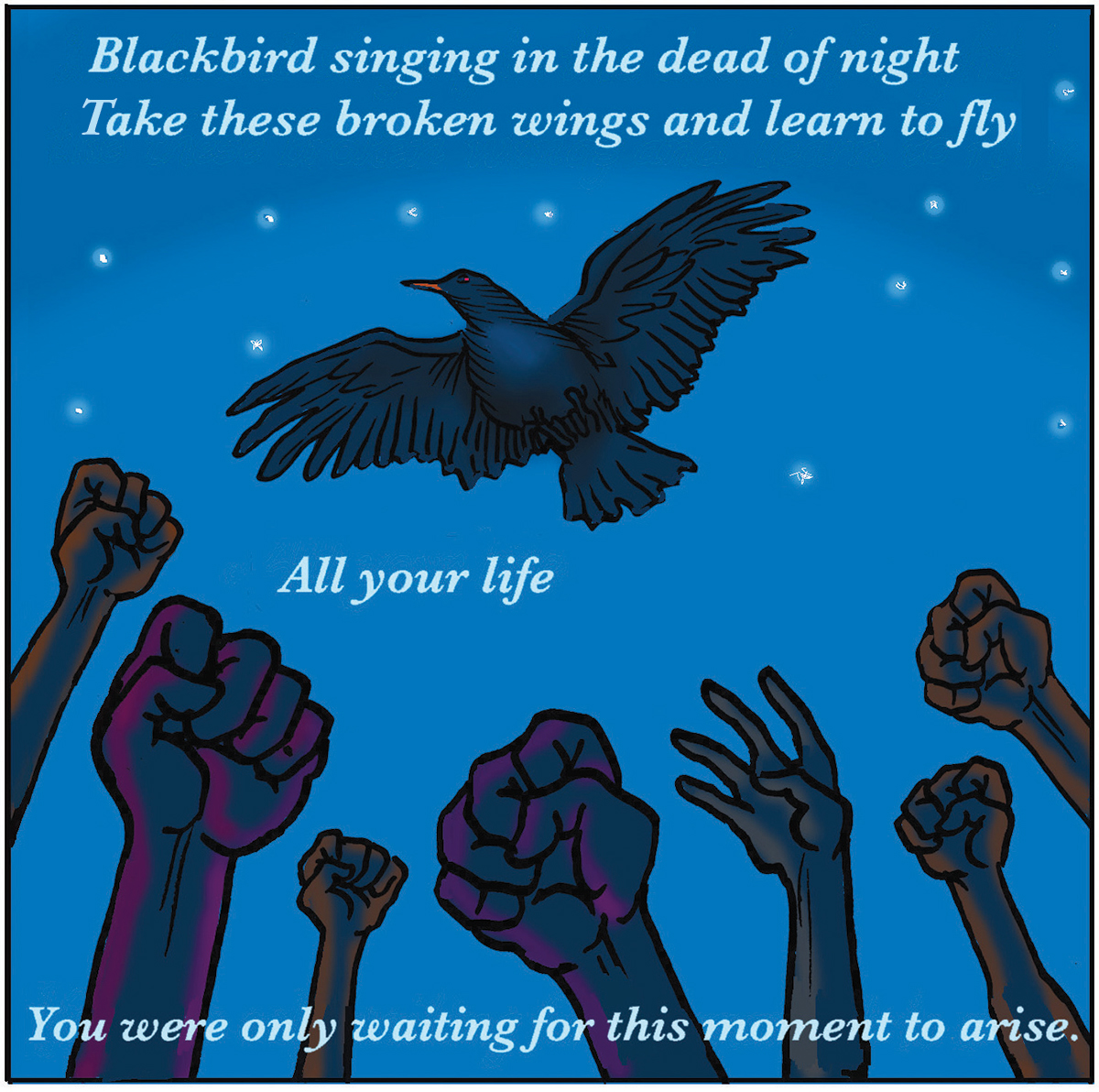

Adapting their song to the environment they find themselves in is just one of the remarkable characteristics of this wonderful bird Scientific name: Turdus merula Length: 24-25cm Wingspan: 34-38.5cm UK numbers: 5.1 million pairs / 10-15 million wintering Habitat: Everywhere Diet: Insects, worms and berries Here’s an admission – the Blackbird’s is my favourite birdsong in all the world.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)